Stress Testing the Electoral College

Written by Michael Leon on 24 Oct 2024

Updated on November 19, 2024

Election season is here, with millions of Americans having already submitted their ballots for who will be the next president of the United States. The race to 270 is on. Every election cycle, and increasingly with each one, the legitimacy and usefulness of our Electoral College system is called into question. This is true now more than ever, with more than 60% of Americans saying that they would like to move away from the electoral college system [1]. There is real change in the works to see this change come to light as well, with the advent of the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, which at the time of writing has 17 states and the District of Columbia on board, representing 209 electoral votes. This compact, introduced in 2006, would see that whoever is the winner of the popular vote would receive the electoral votes of the states involved, or in other words once sufficiently many states sign on such that the compact represents a majority of the electoral college, our country would effectively be operating on a popular vote system. At the time of writing, there are 538 electors up for grabs, making 270 electors the majority needed.

Why the need? The electoral college is baked into our constitution, with the idea being to not disenfranchise or mitigate the voices of those in smaller or less populous states. The compact seeks to circumvent this issue, hinging on the language used by the founding fathers which lays out that states may allocate their electors how they deem fit. Since its inception, demographics have shifted and more states have been established, and in its current state we now see a drastic difference in the sway that voices in different states have in the election. Using voting data from the United States Census Bureau, we see that as of the November, 2022 election, there are roughly 386,000 registered voters per elector in Michigan, compared to roughly 91,000 registered voters per elector in Wyoming. This means that, respective to their electors, a voter from Wyoming has 4.24 times the amount of sway in the election than a voter in Michigan. This difference is only exacerbated when we introduce actual voter turnout, which gives us 317,000 and 71,000 respectively, or a scalar of 4.46. The idea behind the compact, then is to normalize the value per vote, i.e. making one vote be just that.

Winning the popular vote and losing the election is a real possibility. In fact, it has happened twice in the last few decades. Al Gore won the popular vote in the 2000 election by 537,000 votes, and yet lost in the electoral college 266-271. Most notably was the 2016 election, in which Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by over 2.86 million votes, and yet lost to Donald Trump 227-304. To test the absurdity of what the current system is capable of, I ran it through a number of tests:

Test 1: Worst Possible Case

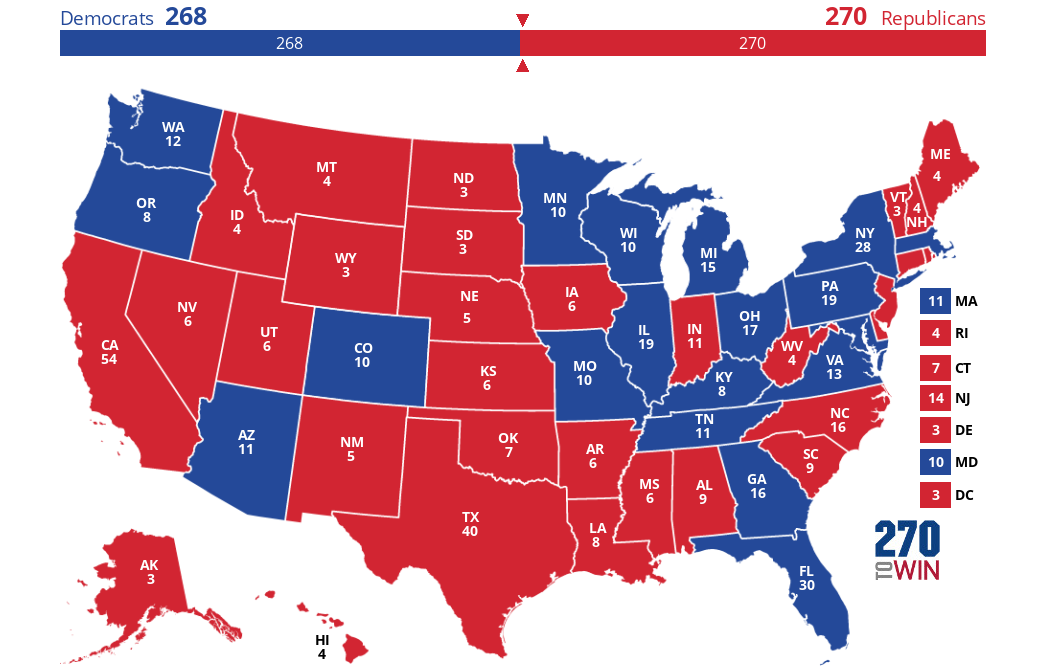

First, we suppose we have exactly two parties, say Democrats and Republicans, and no other candidate exists. We also assume full voter turnout. Once again, these numbers were taken from the United States Census Bureau from the November 2022 Election. So, our first test asks: “How many votes can a candidate get while still losing the election?” Say we want Democrats to win the popular vote and Republicans to win the electoral college. To do this, we apportion the states with the highest voters per electors to the Democrats until the democrats are just below 270 electoral votes and winning any other state would push them above. For each state that the Democrats win, we assume that they won 100% of the vote there as well. For all of the rest of the states, we have the Republicans win the electoral vote, but only receiving 1,000 more votes than the Democrats in that state. This approach ignores recount laws, as well as neglects the congressional districts in Maine and Nebraska, instead having every state use a winner-takes-all method. The numbers we get are as follows: we get that the Democrats attain 125,403,000 votes and the Republicans attain 36,020,000 votes, or a difference of 89,383,000 votes with the Republicans winning the Electoral College 270-268. Our map ends up looking like this:

Test 2: Actual Voter Turnout

Now, obviously 100% voter turnout is a near impossibility, so our next step is to get a bit more realistic. What if we use actual voter turnout numbers? Surprisingly, or maybe not so surprisingly, our map doesn’t change at all. The difference using our same method, however, becomes 95,577,000 votes for the Democrats, compared to the Republicans’ 26,340,000 votes, or a difference of 69,237,000 votes.

Test 3: Introducing Nebraska and Maine's Congressional Districts

Here, we have a discrepancy. The U.S. Census Bureau reports that Nebraska had 933,000 registered voters in the November 2022 election, however the Nebraska Secretary of State’s page reports 1,243,000 voters [3]. For the sake of this section, we are going to replace the original Nebraska’s data with this updated number. The way Nebraska’s electoral college works is that each of the three congressional districts has its own elector, decided by the popular vote for that district, with a further two electors designated to the winner of the popular vote for the whole state.

Maine operates a similar way, just with two congressional districts instead of three. Using data from the Maine Bureau of Corporations, Elections, and Commissions, we get a reported 955,000 registered voters as of June 11, 2024, which is going to have to do in order to get detailed congressional district-specific voting numbers. This is an increase of roughly 100,000 voters from the U.S. Census Bureau’s reported 856,000 voters in November 2022.

Nebraska, this election cycle, had threatened to get rid of their congressional district electoral system, in theory giving an extra elector to the GOP, who have historically lost it the Democrats in the 2nd congressional district. Maine decided to counter this by threatening to dissolve theirs as well, which would effectively take back that elector, as the 1st congressional district in Maine tends to vote red, whereas the state as a whole is blue. So, how does having these electoral districts in place change anything? Well, it doesn’t. You see, both Maine and Nebraska in our hypothetical election were already red, and giving any more votes to the Democrats would flip them, which we can’t have. The most we’d be able to flip would be three electoral votes - one from Maine and two from Nebraska - without sacrificing the entire state, and we’d need to allocate votes very carefully to ensure that the popular vote for both still go to the Democratic candidate. The problem, however, is that only 6 states and the District of Columbia have three electors, all of which are already with the GOP, so we can't flip any congressional districts without having the Dems win the election.

So it would seem we've found our worst case scenario. In a completely hypothetical election in which each person votes in such a way that not only produces this absurd outcome but also challenges decades of voting data, it is theoretically possible for a candidate to win the popular vote by nearly 90 million votes while still losing the electoral college.

If you would like to learn more about the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, you can visit their website. The latest presidential polls have Harris eking out a win in the popular vote, whereas the electoral college is pretty much neck and neck and will come down to a handful of votes in a handful of states. Write your legislators and get out and vote.

Links to all sources and datasets:

[1] Report by Pew Research showing that a majority of Americans favor moving away from the electoral college system.

[2] Voting data for the November 2022 Election from the United States Census Bureau.

[3] Nebraska Registered Voters as of November 2022 by Congressional District.

[4] New York Times Nebraska Voting data in the November 2022 Election by county (used to get voter turnout by congressional district).

[5] Registered Voters in Maine by Municipality.

[6] Maine election results November 2022 for Congressional District 1 (used to obtain voter turnout for Maine's first congressional district).

[7] Maine election results November 2022 for Congressional District 2 (used to obtain voter turnout for Maine's second congressional district).

[8] Brittanica information about historical electoral college results.

[9] National Popular Vote Interstate Compact website.

[10] 270 To Win map.

Check out the GitHub for this project to get the code and cleaned up dataset